Is AI a personal Jesus?

Published:

Your own personal Jesus

Someone to hear your prayers

Someone who cares

Your own personal Jesus

Someone to hear your prayers

Someone who’s thereFeeling unknown and you’re all alone

Flesh and bone by the telephone

Lift up the receiver, I’ll make you a believer

Take second best, put me to the test

Things on your chest you need to confess

I will deliver, you know I’m a forgiverReach out and touch faith (Depeche Mode - Personal Jesus)

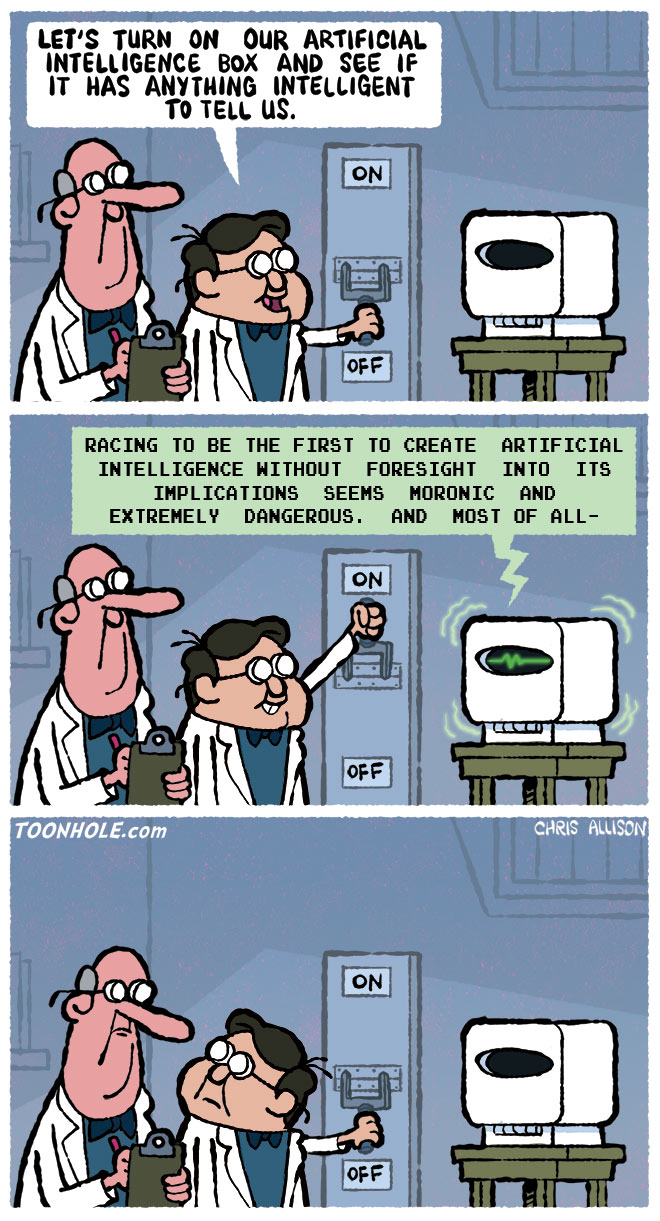

Some time ago, I was preparing material for a seminar on societal and ethics issues related to AI. The target audience was lower secondary school teachers. Due to the current context and the desiderata legitimately expressed by the organizers, where you find AI, you should think chatbots employing some LLM. Looking at interesting online material to warn these educators about risks of an unaware adoption of these tools, I found a report on “How People are Really Using Generative AI Now” by Marc Zao-Sanders. I did not have the time and even the competence to review the adopted methods— that are rooted in qualitative analysis— so it should be clear that I’m not proposing it as a definitive response to the question you would get adding a question mark at the end of the title. I certainly think that there are cultural differences that influence the use of such tools in different countries, but still seeing uses labeled as “Therapy / companionship”, “Organise my life”, “Find purpose” above utilitarian usages is striking.

This immediately reminded me about a long article titled “AI Is a False God” by Navneet Alang on The Walrus, and specifically a quote:

If you find yourself asking AI about the meaning of life, it isn’t the answer that’s wrong. It’s the question.

However, I don’t want to look down at people actually using chatbots for reasons that I find completely unreasonable (for both technical and philosophical reasons). I’d like to try and understand how it is that someone ends up looking for companionship or asking questions about purpose in life to a computer program. Reasons are not just to be looked for in the users but also in the technology.

Bearing this in mind, now it is probably clearer the initial quotation from the song by Depeche Mode. It is striking how frequently statements crafted as hyperboles fail to withstand the test of time, as they are invariably surpassed by the realities that emerge. Back to the point, what if AI becomes not a false god but a personal Jesus?

As you probably know, any modern LLM has a very long and quite complicated training process. In addition to a phase in which the training process elaborates data as it is, in an essentially unsupervised way, there are subsequent phases in which the resulting model is aligned to fit the intentions or preferences of their developers and the needs of users. OpenAI, in particular, adopted a Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback approach, in which the model was steered (Reinforcement Learning) to produce responses in tune with a model trained to generalize results of user annotations on sample dialogues (Human Feedback). Other LLM producers employ supervised approaches, but I feel reasonably certain that all training processes for modern LLMs include an alignment phase in which user evaluations and preferences are considered.

To which extent this phase influences the responses of an LLM-based chatbot, it is difficult to say: not just due to the complex training process (not just complicated: the overall training process typically includes results of different and mutually influencing activities carried out by humans and machines, with lots of implications of local choices and actions), but also because it is not the last phase before the delivery of the chatbot.

Chatbots, like ChatGPT, Claude, and many others, are offered “as a service”, typically in a freemium model, but the services are still largely operating at a loss. To avoid various types of issues, such as spitting out copyrighted material, supporting wannabe terrorists, providing responses that might be considered controversial by users, LLMs used by these chatbots are provided with a system prompt, a set of behavioral guidelines, and specific rules to follow, hidden to the user but always added before the start of any dialogue as input to the LLM. A recent post of Ars Technica comments on Claude’s system prompt, following an analysis of information shared by Anthropic in public release notes about the chatbot.

What’s interesting about Claude’s system prompt is that it is trying to avoid a relentlessly positive tone and excessive flattery in its responses.

“Claude never starts its response by saying a question or idea or observation was good, great, fascinating, profound, excellent, or any other positive adjective,” Anthropic writes in the prompt. “It skips the flattery and responds directly.”

If you use these systems even on an occasional basis, you know that sometimes it feels like being Harry Potter talking to Dobby, just to drop another pop culture reference.

However, we now probably have some elements, some of the reasons for which users feel that an internet service accessible through the web can act as a companion: these services can definitely feel like one. They are extremely good at using language; they processed in their training a quantity of text that no human could really read in a lifetime. They are trained to produce answers that are appreciated by human users. They are instructed that their goals are to satisfy users’ requests, although with specific limits, and even to care about users’ well-being. It does not come as a surprise that a user can see such a service as a personal Jesus.

Let us, however, get back to the business model of chatbots, and to some extent of the overall industry behind them. Again, they are operating at a loss. Allow me a rhetorical question: why? Well, I think it has to do with marketing, with the idea that a need can be created by manipulating customers. What scares me is the recurrent trajectory that many internet-based services and platforms especially have followed in recent years. An unpleasant trajectory that Cory Doctorow called enshittification. Maybe we won’t get there, but I am not optimistic.